CHANS Lab Views by Kai Chan's lab is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://chanslabviews.blogspot.com.

This content was reblogged from Relational Thinking, the People and Nature Blog.

|

| Varied Thrushes have declined by more than 60% over the last five decades. Artwork: © Harold Eyster. |

In short, yes. Coupled with a framing that highlights the interdependent relationships between people and a species, evidence of population differentiation can be a powerful motivator for individual efforts to conserve or restore nature.

Just last week, a Mexican fish that went extinct in the wild in 2003 was reintroduced back into its ancestral habitat. Other endangered species are also doing well—one of the rarest birds in North America, the Kirtland’s Warbler, has seen its population increase by over 1000% since 1970.

But whilst many endangered species have been making a comeback thanks to conservation efforts, widespread and common species have been rapidly dwindling.

Continue to read the rest on Relational Thinking...

CHANS Lab Views by Kai Chan's lab is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://chanslabviews.blogspot.com.

Dear friends, (apologies for cross-posting)

Many of you know that I’ve been at the forefront of science-policy efforts to bring attention to the need for transformative system change. It’s now clear that despite acknowledging this necessity, governments and businesses will not take the needed actions unless there’s an unprecedented coordination to pressure them to do so. Working only in science and science-policy circles left me feeling like a pawn in political theatre of the absurd (see the story here).

So today a powerful little team and I are launching CoSphere, a coalition for system change toward sustainability. Our aim is to bring science to build a community of those passionate about a better future.

The relevant science is the global systems science of where we have leverage and where that’s needed (what to act on), and the science of social transformation to strategize our efforts (how we can act). Millions of people demonstrated their concern for a better future through recent climate protests. Equipped with this knowledge, together we can bring about that future even despite opposition from those seeking to preserve business-as-usual.

My ask: If this resonates, join us, and share this with others. You and they may also be interested in this essay (published in The Globe and Mail), this coverage in the Vancouver Sun, or this Twitter thread. Our partners include David Suzuki Foundation, CPAWS, Canopy, Plastic Oceans, Birds Canada, Raincoast, Y2Y, and more. (If you can bring another organization, please do!)

Bring your passion, your creativity, and your expertise. On the Forum, we seek to create a space where people’s efforts are celebrated, and where we all bring our expertise towards our common objectives. Whereas so many scientists are used to speaking primarily to policymakers and journalists, we hope to create a pathway for science to empower activists and advocates of all ages (including the powerful youth movement).

So we’d love help reaching out to youth leaders. We want to help equip and orient climate groups and environment clubs at universities, high schools, and elsewhere.

In solidarity,

Kai

PS, Since we’re brand new, you’ll see that some places feel incipient (e.g., the Forum). We welcome your contributions to make it an inviting, vibrant space. KC

--

Kai M. A. Chan, Professor and Canada Research Chair—Rewilding and Social-Ecological Transformation (he/him)

CHANS Lab (Connected Human-and-Natural Systems) CoSphere (now launching)

Coordinating Lead Author, IPBES Global Assessment

Lead Editor, People and Nature—a BES journal of relational thinking

Royal Society of Canada College of New Scholars—member

Leopold Leadership Fellow; Global Young Academy alum; Canada’s Clean16 for 2020

Institute for Resources, Environment & Sustainability

The University of British Columbia | Vancouver Campus | Musqueam Traditional Territory

AERL Rm 438, 2202 Main Mall | Vancouver, BC | V6T 1Z4 Canada

Ph: 604.822.0400 Fax: 604.822.9250

kaichan@ires.ubc.ca kc@kchan.org

www.ires.ubc.ca Blog: CHANS Lab Views

@KaiChanUBC My group: chanslab.ires.ubc.ca

Google Scholar Confidential: for intended recipients only

Recent papers: Kreitzman et al., Ecosphere, Woody perennial polycultures enhance biodiversity and ecosystem functions

Bullen et al., Global Ecol. Biogeogr., Ghost of a giant (Steller’s sea cows) (Hakai Magazine)

Naito et al., Sust. Sci., An integrative framework for transformative social change

A Story by Alanna Mitchell

I remember the moment I let myself glimpse that I was deeply, intimately involved in the work of healing the planet. It was nearly two decades ago, as I sat down to write the first words of my first book, Dancing at the Dead Sea.

I had spent a year travelling the world as a journalist with Canada’s national newspaper, The Globe and Mail, as a self-styled earth sciences reporter. The stories from those adventures had garnered me a couple of international awards and a fellowship at Oxford University where I studied with the late Norman Myers. He was, I always reckoned, a Cassandra. He was one of the first scientists to flag our current extinction spasm, the looming tragedy of environmental refugees and the fact that so much of the planet’s biodiversity rests in a few small and precious hotspots. Hardly anyone believed him. Yet he kept going, a cranky soothsayer of the Anthropocene.

And as I sat down to begin crafting that first book, so much of which had been shaped by him, I panicked. I had written the newspaper stories in the conventional way: as a journalistic observer of the information. At a remove. As if I were not also a citizen of this planet and affected by all this information I was unearthing.

Should I write this book in the uninvolved third person, or the passionately involved first? Did I even have the right to write it in the first person, as one implicated in the story? A crisis of faith. I sat at my keyboard – tucked away in a corner of my bedroom in Toronto – and pressed capital I. The book was first-person. I was in.

Myers had already taught me that the real story was about the systems our species had set up – energy, food production, finance, governance. And that what was at stake was the life support systems of our planet: the marvellous dance of creatures, the hydrological cycle, the climate, the ocean. All the small stories added up to something far bigger than the sum of their parts. We need to be on the planet as if we mean to stay, he always used to tell me.

It was a small leap from that first book to a one-woman play. Well, philosophically, if not practically. I had already quit my newspaper job – “What part of ‘NO’ don’t you understand,” one of my editors barked at me shortly before I quit, when I asked once again to write stories about the changing sea – and spent three years on 13 journeys around the world with scientists to interrogate the state of the ocean. It turned into my second book, Sea Sick: The Global Ocean in Crisis.

|

| Scanning the horizon is crucial, but can be overwhelming. There's a lot out there! Photo: Kai Chan |

|

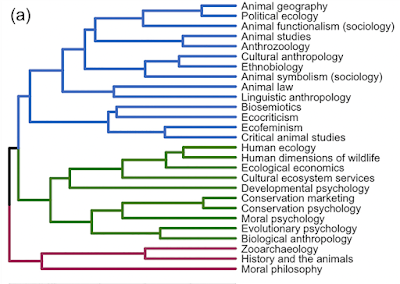

| Echeverri et al. found 27 different fields of human-animal relations. |

|

| An example of human-animal relations (and values): I feel a sense of responsibility and kinship for orcas, hence this Father's Day card from my daughter. |

|

| Relational values are an example of a theme that straddles many fields, disciplines, and domains. But it's key to relate them to other kinds of values, as we did in Chan et al. (2018). |

By Kai Chan

This is part of a series, How to Write a Winning Proposal—in 10 Hard Steps

The true first step in writing a winning proposal is to identify the (research) problem. Lots has been written about how to identify a good problem, e.g., as a puzzle. For our purposes, though, that step is WAY down the road.

Or rather, identifying a good problem is a crucial and complex process that we’re going to unpack into several steps over the coming posts. But in order to engage in those steps, you need an anchor—a tentative topic or problem—that you can use to ground you through the coming exploration.

But how do you decide on that tentative topic/problem? It’s a chicken-and-egg dilemma: to identify a good topic/problem you need a tentative topic/problem.

|

| Choosing a topic/problem is a chicken-and-egg dilemma (you need a tentative one to investigate possibilities), but there is a place to start (read on). ruben alexander, Flikr |

They’re not wrong. They’ve just skipped a key step—in my opinion. And they’re misleading.

They are misleading because there is no such thing as a “under-explored aspect … or area”. Every research area is simultaneously over-explored if it isn’t interesting or important to you, and under-explored for those who find it interesting and important.

There’s only one way to identify a good tentative topic/problem. It’s not to survey the literature or the world around you—it’s to look within. That is, start from your critical ingredients. A good tentative topic is one that would be meaningful to you.

The other authors above would likely agree that looking within—at what you find meaningful—is a good place to start. They likely just think it goes without saying. Having supervised dozens of students and taught twenty in two iterations of this course (RES 602), I know that it still needs to be said.

|

| Low-hanging cashew fruit. (Did you know that cashews had delicious fruit? They do, and this is thanks to gomphotheres and other prehistoric megavertebrates, which relates to rewilding.) Photo by form PxHere |

You can’t spot great, easy opportunities (the low-hanging fruit) without really getting to know a field. Those externally-obvious low-hanging fruit have mostly been picked.

There’s no research area that is truly saturated—that doesn’t have a genuine research opportunity. There are areas that are very competitive, there are ones whose methods won’t appeal (e.g., because they are too theoretical, too dependent on fieldwork, or too deeply statistical). But this is all a function of fit with what ‘turns your crank’.

Following apparent low-hanging fruit is unlikely to allow you to develop the methods that are most important to your future, or to enable you to develop connections with your key communities of research and practice, or to jibe with a theory of change that resonates with you. That is, they are unlikely to deliver your critical ingredients.

So start with your critical ingredients, and fine-tune your good tentative problem into a good problem (see steps 2-6 in this series).

But how exactly do a handful of critical ingredients deliver a research problem? At the nexus of each critical ingredient, there is a quadrant in n-dimensional space that represents the set of your most meaningful problems.

For me, this is a project involving the conservation and/or restoration of nature alongside its sustainable use (fields) with a combination of ecological and social dynamics (disciplines), using quantitative and qualitative methods (tools) in southwest British Columbia (geographical study areas). It will engage with values and rewilding in the context of transformative change (theories of change, questions).

So, once you’ve completed the critical ingredients document, the task is to simply layer the various dimensions as I’ve done just above: the promising "problem" is the intersection of your critical ingredient fields, disciplines, tools, study areas, theories of change, and questions.

Next we’ll discuss how to use this starting point to explore the beautiful landscape of research opportunities and approaches.

Next up: What Is a Horizon Scan? (Step 2) + Why You Need To Do One Now

Previous: Why You Need a Theory of Change

The Intro to this series (with links to the full set): How to Write a Winning Proposal—in 10 Hard Steps