Years or months from now, you’re defending your dissertation/thesis, and one of your examiners frowns. You tremble as they ask, “What you’ve discovered is pretty normal in [field H]. But you haven’t even discussed [that field], or cited any of the key papers. Why not?”

|

| Scanning the horizon is crucial, but can be overwhelming. There's a lot out there! Photo: Kai Chan |

Or maybe it’s, “Have you ever heard of [method Q]? It seems like it would have saved you loads of time and provided a much more robust basis for your conclusions.” Or any number of other scenarios of overlooked studies, fields, or methods.

Such a moment of chagrin is largely due to a failure to scan the horizon. Avoiding such moments is why you might conduct a horizon scan right now—whether you’re just starting or well underway.

For student X (a concrete anonymized example), an oversight like this was very costly. X was studying zoonotic disease risk and its various causes. A central finding was the large gap between the spatial distributions of the physical prevalence of risk and of people’s concern. But X hadn’t engaged at all with the risk perception literature, where such findings are well documented and also well understood. X had entered the problem as a zoologist seeking to expand into social-ecological problems. It simply hadn’t occurred to X that there was a general literature on risk. For X, this meant a brush with failure, and the need for major revisions. What should have been a triumphant moment was nearly the exact opposite.

Domain/Topic

Domains are the broad problem of focus—e.g., biodiversity conservation, just climate transitions, sustainable fisheries, or endocrine-disrupting chemicals. The domain or topic aligns closely with interdisciplinary research fields, where many different methods might be applied, potentially from many different disciplinary backgrounds. But sometimes—as with Echeverri et al. (2018)—the domain is

much broader than a single field. Within a domain, it’s important to understand how others are growing knowledge about similar problems. A

forthcoming paper in

Sustainability Science led by

Rumi Naito (with

Jiaying Zhao and I) demonstrates the kind of insights that can be gained by a deeply interdisciplinary analysis of the illegal wildlife trade.

|

An example of human-animal relations (and values):

I feel a sense of responsibility and kinship for orcas,

hence this Father's Day card from my daughter. |

Methods

Methods are the tools for collecting and analyzing data to answer research questions (e.g., system modeling, multivariate statistics, surveys, document analysis). Any given method might be applied in a wide variety of contexts and disciplines, and understanding this diversity of applications can yield new insights and approaches. This

great paper by Paul Armsworth lays out how economists and ecologists use similar statistical regression methods quite differently, and why. Meanwhile, the use of narrative elicitation (developed earlier) led to crucial insights in the field of ecosystem services (thanks to

Terre Satterfield; see

here,

here and

here). Insightful guidance for mixed-methods research—which is common in sustainability science and interdisciplinary environmental research—can be found in

Creswell & Creswell 2005.

Themes

Themes are concepts and constructs that cut across domains and methods (e.g., risk, values, power, resilience, telecoupling, markets, neoliberalism). They represent another key pathway by which learning can bridge from one domain to another. E.g., Leslie and McCabe (

2013) demonstrate beautifully how response diversity can yield resilience in social systems (not just ecological ones). The idea of

relational values was intended to enable tremendous insights to overflow from the coming together of several domains and multiple disciplines, as in

this special issue.

|

Relational values are an example of a theme that straddles many

fields, disciplines, and domains. But it's key to relate them to other

kinds of values, as we did in Chan et al. (2018). |

But how to actually conduct a horizon scan? There’s no single recipe. When there’s no map of a landscape, many kinds of explorations can be fruitful. In basic terms, having identified your domain/topic, possible methods and themes—and a wide variety of terms to represent these—do the following to get a sense of what key reviews/papers/fields/terms you might be missing:

- Surround yourself with diverse like-minded folks researching similar problems and themes, from a variety of vantage points.

- Talk with your supervisor(s) and committee members, and other experts.

- Talk with fellow students about your work and theirs.

- Search the academic literature using your keywords without too much constraint (i.e., without applying ‘and’ links, so without restricting to spaces you know) (using ISI Web of Science, Google Scholar, etc.; see Paperpile and UBC library for tips).

- Follow chains of citations (backwards and forwards: sources cited by key papers; and sources citing those key papers—Connected Papers might be helpful for depicted citation links across sources).

A key point is not to let yourself read deeply during this step. Drilling down in one part of the landscape will distract the exploration of broader horizons. It may help to distinguish 'scanning' from 'exploring', and iterating between these phases. In the superficial phase of scanning you might focus on finding new literatures while also taking notes about particular papers, books and fields to explore more fully.

Similarly, don't let this step drag on for too long. Do it in a time-bounded way in one burst, and then do it again later in fits and spurts. You can never really finish scanning the horizon. The idea of 'saturation' is elusive here (that you've reached saturation if searches repeatedly reveal the same sources), because this can result from searching in a rut rather than getting out to the broader landscape. But don't sweat it; people will forgive you if you gave horizon-scanning an honest effort but still missed some features of interest.

Scanning horizons promises to vastly improve your research and its reach, and to prevent the worst moments of chagrin.

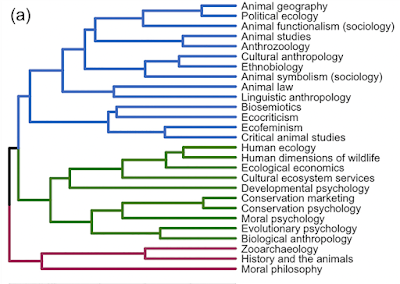

But much more importantly, horizon scans can enable you to help facilitate great insights well beyond your own research, by bridging parts of this deeply fractured academic landscape that remain isolated. This hope is what led us (the editors of

People and Nature) to state in our

opening editorial that "People and Nature thus aspires to be not a collection of unlike contributions to different literatures, but rather the nexus where these various literatures about human‐nature relationships convene."

CHANS Lab Views

CHANS Lab Views by

Kai Chan's lab is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at

https://chanslabviews.blogspot.com.